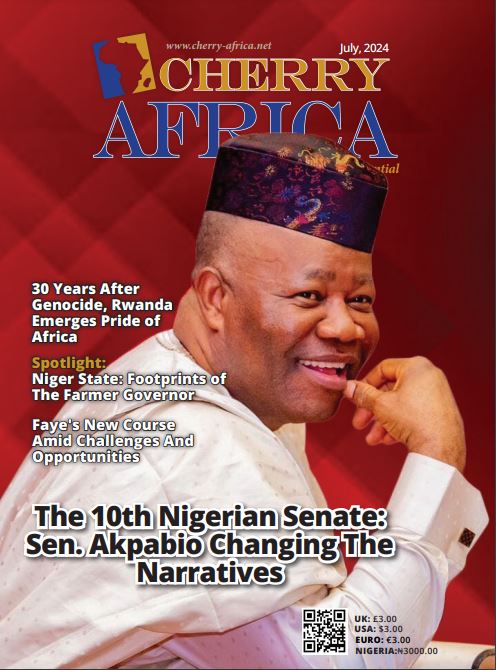

The experience of genocide in Rwanda may be loathsome, but it’s also loaded with takeaways to guide Africa and the rest of the world in handling conflicts and embracing peace writes Carolyn Isaac

In 1994, Rwanda, a small East African country, experienced one of the most brutal, horrific and systematic massacres in human history. About 1,000.000 people, mostly Tutsis and moderate Hutus were gruesomely murdered over the course of 100 days (April-July 1994) by their brothers, friends and neighbors of Hutu extraction.

The genocide which was conceived by extremist elements of Rwanda’s majority Hutu population, who plotted to kill the minority Tutsi population and anyone who opposed those genocidal intentions, was a culmination of a long history of ethnic tension and political conflicts among the gregarious ethnic groups of Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda – mere intricate placental extensions you may say. It is estimated that about 200,000 Hutus, incited by propaganda from various media outlets and highly influential and respected personalities in the society, participated in the genocide that claimed the lives of over almost 1,000,000 Tutsis in Rwandan.

About 2,000,000 Rwandans fled the country during and immediately after the genocide.

BACKGROUND

Rwandans are made of three distinct ethnic groups. The major ethnic groups in Rwanda being the Hutus and the Tutsis, respectively accounting for more than four-fifths and about one-seventh of the total population.

A third group, the Twa, constitutes less than 1 percent of the population. These three groups speak same language (Kinyarwanda), suggesting that they have lived together for centuries. Social differences between the Hutu and the Tutsi traditionally were profound, as shown by the system of patron-client ties (cattle contract) through which the Tutsis, with a strong pastoralist tradition, gained social, economic, and political ascendancy over the Hutus, who were primarily agriculturalists.

Still, identification as either Tutsi or Hutu was fluid. While physical appearance could correspond somewhat to ethnic identification, the Tutsis were generally presumed to be light-skinned and tall, while the Hutus were dark-skinned and short.

The difference between the two groups was not always immediately apparent, because of intermarriage and the use of a common language by both groups. During the colonial era, Germany, and later Belgium, assumed that ethnicity could be clearly distinguished by physical characteristics and then used the ethnic differences found in their own countries as

models to create a system whereby the categories of Hutu and Tutsi were no longer fluid.

The German government continued pursuing a policy of indirect rule that strengthened the dominance of the Tutsi ruling class and the absolutism of its monarchy. Some Hutus began to demand equality and found sympathy from Roman Catholic clergy and some Belgian administrative personnel, which led to the Hutu revolution. The revolution was followed by months of violence. Many Tutsis were killed in the process, while others fled the country. In 1961, a Hutu coup was said to have been carried out which led to the deposing of the Tutsi king, who had already fled the country due to violence in 1960. The Tutsi monarchy was officially abolished.

Rwanda became a republic, and an all-Hutu provisional national government came into being. Independence was proclaimed the next year, 1962. The transition from Tutsi to Hutu rule was not peaceful. From 1959 to 1961, about 20,000 Tutsis were killed, and many more fled the country. By early 1964 at least 150,000 Tutsi were in neighboring countries. Additional rounds of ethnic tension and violence flared periodically and led to several killings of Tutsis in Rwanda, between 1963, 1967 and the later part of 1973.

THE INVASION

Tension between Hutu and Tutsi flared again in 1990, when Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) rebels invaded Rwanda from Uganda. A cease-fi re was negotiated in early 1991, and negotiations between the RPF and the government of longtime president Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, began in 1992. An agreement between the RPF and the government, signed in August 1993 at Arusha, Tanzania, called for the creation of a broad-based transition government that would include the RPF.

Hutu extremists were strongly opposed to that plan. Dissemination of their anti-Tutsi agenda, which had already been widely propagated via newspapers and radio stations for a few years, increased and would later serve to fuel ethnic violence.

THE GENOCIDE:

In the evening of April 6 1994, a plane carrying the Rwandan president Juvenal Habyariamana, a Hutu and Burundi president Cyprian Ntaryamira, also a Hutu was shot down over Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, killing everyone on board. The perpetrators of the attack were never conclusively identified but it triggered a wave of organized and brutal killing of Tutsis and moderate Hutus that night by Hutu militias and government forces. Prime Minister, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, a moderate Hutu, was assassinated the next day, as were 10 Belgian soldiers (part of a United Nations Peacekeeping Force already in the country) who were guarding her.

Her murder was part of a campaign to eliminate moderate Hutu or Tutsi politicians, with the goal of creating a political vacuum and thus allowing for the formation of an interim government of Hutu extremists. The speaker of the National Development Council (Rwanda’s legislative body at the time), Theodore Sindikubwabo, became interim president on April 8, and the interim government was inaugurated on April 9. The next few months saw a wave of anarchy and mass killings, in which the army and Hutu militia groups played a central role. Radio broadcasts further fueled the genocide by encouraging Hutu civilians to kill their Tutsi brethren, who were referred to as “cockroaches” that needed to be exterminated, babies were not spared.

METHOD OF KILLING

The methods for killing were typically quite brutal, with crude instruments often employed to pummel or hack away victims. Machetes were commonly used. Rape was also used as a weapon and included the deliberate use of perpetrators infected with HIV/AIDS to carry out sexual assaults on women of Tutsi extraction.

The United Nations (UN), which already had peacekeeping troops in the country for a monitoring mission (United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda; UNAMIR), made unsuccessful attempts to mediate a ceasefire.

THE WITHDRAWAL

On April 21, as the crisis deepened, the UN voted to reduce UNAMIR’s presence in the country from 2,500 troops to 270. That seemingly incomprehensible troop reduction at a time when assistance was sorely needed was rooted in such factors as the mission’s mandate, which required an effective cease-fire to be in place, and the inability of the UN to find more troops to bolster the mission, which it felt had already been stretched too thin to have a significant impact on the situation.

On May 17, however, the UN reversed its decision and voted to establish a force of 5,500, composed of soldiers mainly from African countries, but those additional troops could not be immediately deployed. On June 22, the UN backed the deployment of a French-led military force, known as Operation Turquoise, into Rwanda to establish a safe zone; the operation was opposed by the RPF, which claimed that France had always supported the government and policies of President Habyarimana.

The RPF had earlier rejected the legitimacy of the Hutu extremist interim government inaugurated in April 9 and resumed fighting. By April 12, RPF troops had invaded the outskirts of Kigali. The RPF were successful in securing most of the country by early July, taking Kigali on July 4. Extremist Hutu leaders, including those of the interim government, fled the country.

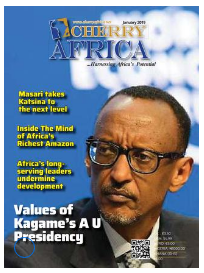

A transitional government of national unity was established on July 19, with Pasteur Bizimungu, a Hutu, as president and RPF leader, Paul Kagame, a Tutsi, as vice president.

The genocide had come to an end. The end of the genocide was followed by a massive humanitarian crisis. Millions of Hutus fled to neighboring countries, fearing retaliation. Many of them were said to have died of diseases and violence in overcrowded camps. As soon as the genocide was over, the country faced years of reconciliation and recovery. Trying those who were thought responsible for genocidal acts was a primary focus, as was promoting national unity and rebuilding the country’s economy.

Those accused of participating in the genocide were primarily tried in one of three types of court systems: the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), Rwandan National Courts, or Local Gacaca Courts. Some suspects who had fled Rwanda were tried in the countries in which they were found.

THE TRANSITION

In 2000, Bizimungu resigned from the presidency. Following his resignation, the Supreme Court ruled that Kagame should become acting president until a permanent successor was chosen. Kagame had been de facto leader since 1994, but focused more on military, foreign affairs and the country’s security than day-today governance. Kagame ran for office in 2003 on the platform that emphasized national unity and moving beyond ethnic divisions.

He was elected President in 2003 and has since been a key figure in Rwanda’s rebuilding and reconciliation efforts following the 1994 genocide. Kagame’s leadership has been marked by efforts to promote national unity and reduce ethnic tensions.

READ THE FULL STORY IN OUR MAGAZINE BELOW